1. Introduction

Every company wants to guard its assets from hackers and cyber-terrorists. Even the most advanced technological security cannot protect an organization from a cyber breach if the people in the organization are not careful and protective. In 2017 alone, there were 541 major, publicly reported data breach incidents in which 1,922,663,085 records were compromised [1]. According to the 2018 Cost of a Data Breach Study by Ponemon, the average cost of each lost or stolen record containing sensitive and confidential information also increased to $148 [2]. However, in today’s cyber world, it only takes one employee clicking on a phishing email to provide an attacker with an entry point into the systems running a business. Once inside, an attacker can lock up critical information, as seen in the WannaCry virus, or bring down critical infrastructure as in the Ukraine, when the Petra attack took nuclear radiation monitoring offline, or more commonly, result in a data breach incident [3].

Insider threat from human behavior is one of the most difficult aspects of security to control. Building a culture of cybersecurity within an organization guides employee behavior and increases cyber resilience. A culture of cybersecurity underlies the practices, policies and “unwritten rules” that employees use when they carry out their daily activities. The Chief Information Security Officer (CISO) at Liberty Mutual, explained why he felt the need to invest in a culture of cybersecurity: “it only takes one mistake from an employee clicking a wrong link or email to erase all the good work done by our professionals. Since a hacker can potentially go wherever they want once they are inside our systems, they can potentially compromise our entire investment.”[4] The global director, enterprise security and risk management at Johnson & Johnson said “When I took over this role, the first thing I asked is 'what's the [people and culture] strategy that we've been following?”[5] Creating a cyber-resilient culture within an organization to mitigate this “weakest link” is on the executive agenda [3] .

However, though cybersecurity culture has a profound impact on risk, it can be difficult to identify, build, and quantify [6], [7]. Examining other kinds of organizational culture provides a foundation for a model of cybersecurity culture. For example, many organizations have developed a robust safety culture [8] where every employee knows, and receives constant reminders, of ways to stay safe and decrease the chance of accidents.

A similar goal can be said for cybersecurity; every employee must act in ways that keep the organization cybersecure. This project presents a practical framework for managing the intangible factors of a cybersecurity culture, focusing on the research question ‘How can leaders understand, shape and align the beliefs, values, and attitudes of their organization with cybersecurity goals?’ In this paper, we outline a model of cybersecurity culture, developed through literature review and workshop practice. The model outlines managerial levers through which the culture can be built and observed. To illustrate how this model works in practice, we describe how financial services firm Liberty Mutual has created a “culture of data protection” which increased cyber resilience in their organization.

This paper contributes to information security practice in three major ways. First, based on theoretical study and workshop results, it provides a way to observe and measure cybersecurity culture. Second, an in-depth case study provides a rich example of how one company created this culture. Finally, it helps managers understand decisions they can make to change cybersecurity culture.

2. Organizational Cybersecurity Culture

To build a model of cybersecurity culture, we examined three concepts: organizational culture, national culture and information security culture.

A common definition of organizational culture comes from Ed Schein’s model [9]. He suggests three components of culture: 1) the belief systems forming the basis for collective action; 2) the values representing what people think is important; and 3) Artifacts and creations which are the “art, technology, and visible and audible behavior patterns as well as myths, heroes, language, rituals and ceremony.”

Using a different lens, Quinn’s competing values- model distinguishes between four types of organizational culture based on the orientation of the values and beliefs [6], [10]: 1) The support orientation emphasizes employee’s spirit of sharing, cooperation, trust individual growth and the decisions made through informal contacts. 2) The innovation orientation emphasizes that the organization is open to change and willing to search for new information, and creative in problem solving. 3) The rules orientation emphasizes the respect for authority, formal procedures, and the importance to follow the written rules, normally resulting into a top-down hierarchical structure. 4) The goal orientation emphasizes the clear specification of the targets, the criteria for performance measurement and the reward based on the attainment of goals, reflecting the understanding of organizational goals, individual responsibility and accountability.

National culture focuses on a cross-cultural perspective and impacts how employees comply with authority and follow organizational rules and policies. The most accepted taxonomy of national culture, by Hofstede, includes concepts such as “individualism vs. collectivism,” “long-term vs. short-term orientation” and “indulgence vs. restraint” [11].

Information security culture, a subculture of an organization’s culture, has been defined by Da Veiga and Eloff [12] as: “attitudes, assumptions, beliefs, values and knowledge that employees / stakeholders use to interact with the organization’s systems and procedures at any point in time. The interaction results in acceptable or unacceptable behavior (i.e. incidents) evident in artifacts and creations that become part of the way things are done in the organization to protect its information assets. This information security culture changes over time”. Essentially this says attitudes, assumptions, beliefs, values and knowledge drive employee behaviors related to the organization’s information and information systems.

While focused on the security of an organization’s data, networks and systems, the concept of cybersecurity culture differs in a fundamental way from an information security culture. According to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) [13] definition, Information security was defined as “the protection of information and information systems from unauthorized access, use, disclosure, disruption, modification, or destruction in order to provide confidentiality, integrity, and availability,” while cybersecurity is the “ability to protect or defend the organization from cyber-attacks”. Information security culture emphasizes behaviors that comply with information security policy, but a cybersecurity culture includes not only compliance with policy, but also personal involvement in organizational cyber safety. In this paper, we define organizational cybersecurity culture as “the beliefs, values, and attitudes that drive employee behaviors to protect and defend the organization from cyber attacks.”

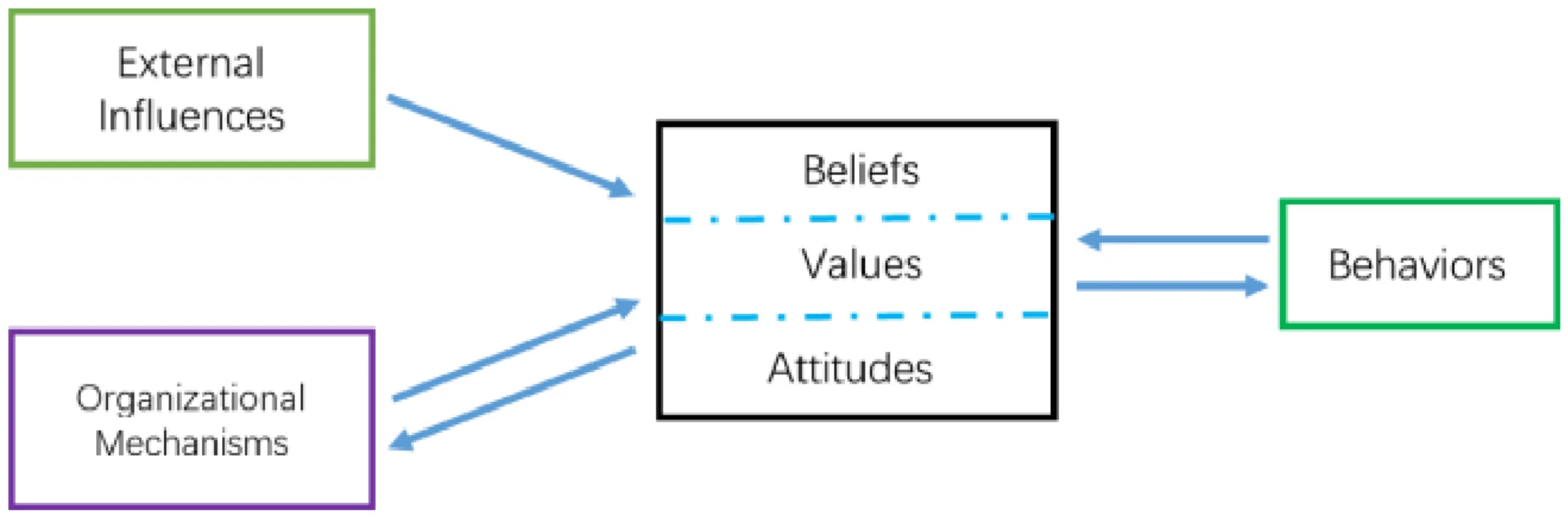

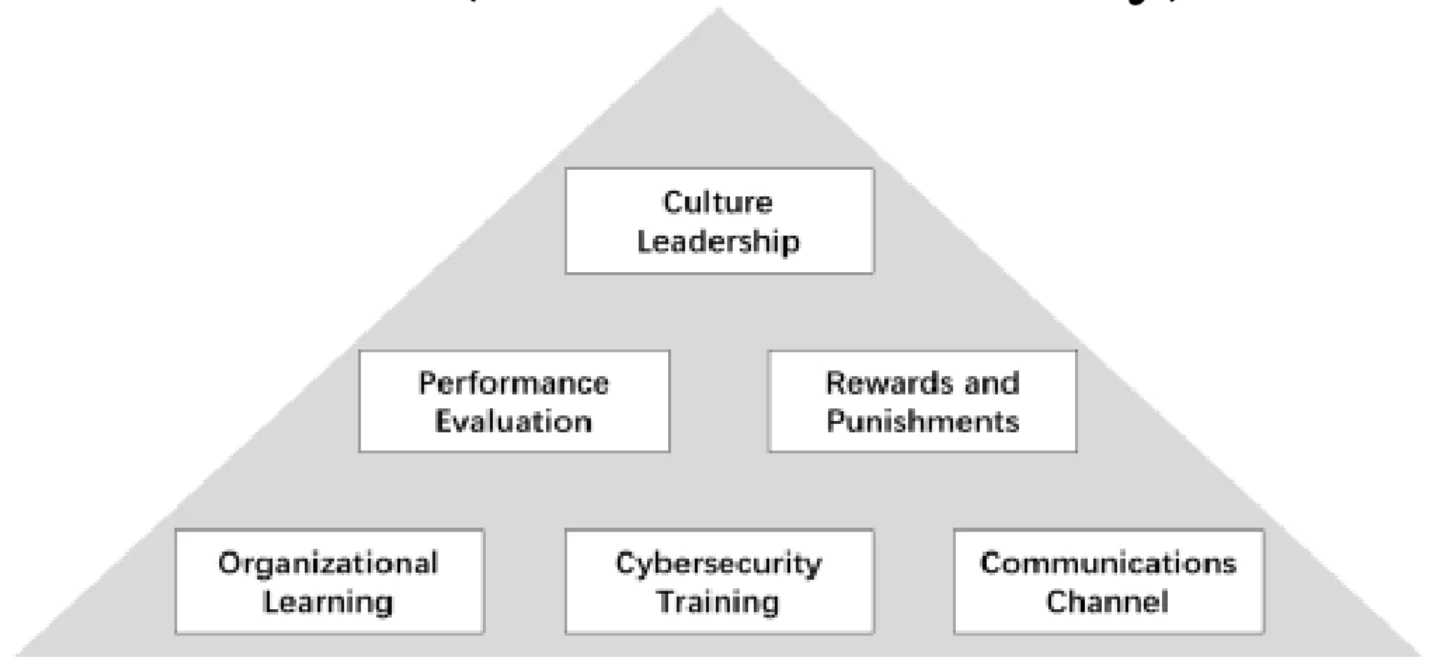

3. Cybersecurity Culture Model

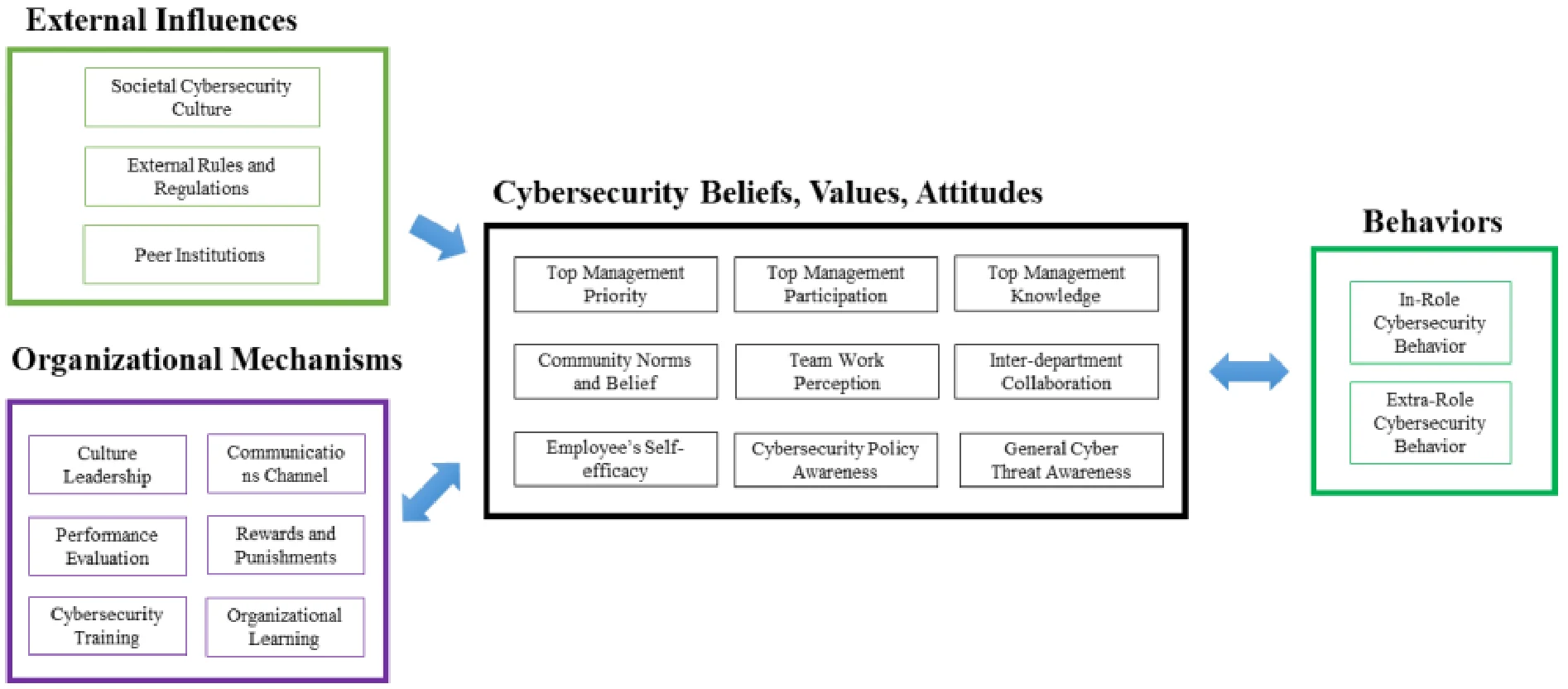

The ultimate goal for manager is to drive cybersecure behaviors. That is achieved, in part, by creating an organizational cybersecurity culture (the beliefs, values and attitudes). The culture, in turn is influenced by both external factors outside the control of managers, and internal organizational mechanisms that managers use. Figure 1 summarizes the top level conceptual framework of the model.

The rest of this section will dive deeper into the model, describing each of the constructs in more detail. We include our definition for each construct based on literature[1] and the outcome of interviews with focus groups. Participants in the focus groups, including 60 senior executives, managers and researchers from large, global and US-based companies from multiple industries and key cyber security solution providers[2], were asked to share ways their organization encourages cybersecurity behaviors. Their insights were then used to fine tune the constructs in our model.

3.1. Behaviors

Since cybersecurity is more than a technical issue, organizations need to rely on the employees’ behaviors to prevent and protect the organization from potential cyber-attacks. Ultimately, employee behavior is what creates or reduces cyber-based vulnerability. Two types of behaviors are the outcomes of a cybersecure culture: in-role and extra-role behaviors.

In-Role Cybersecurity Behaviors refers to the actions and activities an employee takes as part of their official role in the organization. These in-role cybersecurity behaviors such as complying with formal organizational security policies, decreasing the computer abuse, and avoiding policy violation, are critical to securing the organization.

Extra-Role Cybersecurity Behaviors refers to actions and activities an employee does that are not part of their job description. Two major types of extra- role behaviors include helping, referring to the cooperative behavior to aid others who might ask a cybersecurity question, and voicing, referring to speaking up to offer comments and knowledge to improve cybersecurity. Extra-role cybersecurity behaviors, particularly the voicing behavior, can be very valuable since cyber space is a complex environment and threats show up at every level of the organization. For example, security leaders value new ideas, as well as knowledge about emerging vulnerabilities and ways to continuously improve the organizational cybersecurity.

3.2. Beliefs, Values and Attitudes

At the heart of the model is the cybersecurity culture. Values, attitudes and beliefs are unwritten rules that everyone knows but few can articulate. However, they can be observed in actions taken by leaders, groups, and individuals in the organization. Figure 2 summarizes nine constructs that make up the culture for these three organizational levels. Note that the rows in this figure are not meant to align individually with beliefs, values and attitudes. Collectively they represent these constructs.

The leadership in an organization plays a significant role in creating and propagating the organization’s culture. Top management are both the mechanism to stop external forces from impacting the organization, and the decision maker for investing limited resources. In addition, leaders set an example for others which influences cognitive beliefs. When employees see leaders prioritizing and participating in cyber-security activities, it influences employees own involvement.

Further, a resource-based view suggests that the leader brings perspectives, skills and information to the organization and positively influences the development of a shared understanding, in turn leading to strategic alignment with the business. When leaders have information about keeping their organization cyber secure, they act in ways that increase cybersecurity, and are more likely to share that information with others in the organization. Hence, to understand this aspect of a cybersecurity culture, we include three constructs to assess the quality of cybersecurity culture among leadership:

Top Management’s Priorities: When top managers believe that cybersecurity is important, they will make cybersecurity a priority for the organization. This is seen in strategic discussions, and in decisions leaders make about allocation of resources.

Top Management’s Participation refers to the top management’s personal involvement in the cybersecurity-related activities. Participation could be in the form of communicating cybersecurity policies and attitudes or in actions that specifically secure the organization like funding/attending training, creating games, participating in other cybersecurity activities.

Top Management’s Knowledge refers to the cybersecurity-related knowledge, skills and competencies leaders have. Leaders who know and understand their cybersecurity vulnerabilities are more likely to have values, beliefs and attitudes around building a more cyber resilient organization.

At the group level, organizations are made up of people who work together to execute business processes that make up the activities of the business. Groups of individuals collaborate, create, and communicate. By doing so, they build shared values and beliefs that are artifacts of culture. Three constructs summarize the group level attitudes, values and beliefs:

Community Norms and Beliefs refers to the collective set of ideas the group has about cybersecurity. All groups have norms and those influence what the individuals in the group believe. Many theories, including the social control theory, theory of planned behavior and technology acceptance model all emphasized the influence from social environment on an individual’s beliefs and attitudes. We can apply this to cybersecurity culture. For example, if the group values information protection, individuals in the group will more likely value information protection.

Teamwork Perception refers to the way teams within the organization work together to be more cyber secure. Shared team cognition theory, emphasizing the importance of team members being “on the same page,” and interactive team cognition theory, arguing that teams are cognitive systems in which cognition emerges through interactions and team situation awareness is much more than the sum of individual situation awareness, highlight the way team perceptions come together. To be situationally aware about a cybersecurity threat, team collaboration provides a way to continuously process and update information. For example, a team working together on a business project might also build in cybersecurity considerations in their activities, which demonstrates that they value cybersecurity.

Inter-department Collaboration refers to the work done between groups of individuals from different parts of the organization. For example, there might be an individual in each department participating on a task force to find ways to be more cybersecure across the organization. To response to the increasing data breach incidents over these years, the information security sectors and the business sectors need to work closely with each other. Recent research suggests that the cybersecurity leader’s scope of responsibility now extends beyond the IT department to logistics, business continuity and corporate change management further increasing inter-department collaboration.

Newcomers to a group are socialized by the members, making group norms a strong component in shaping values, beliefs and attitudes. Involvement by the information technology organization and the information security organization is expected in most organizations. However, involvement beyond the cybersecurity professionals in discussions, issues and activities of cybersecurity is an indicator of higher value placed on cyber resilience in the organization.

The third set of constructs within an organization’s cybersecurity culture are the individual beliefs of employees. This includes understanding of cyber threats, awareness of organizational cybersecurity policies, and knowledge of personal capabilities to impact security (self-efficacy). When individuals understand and know how to act, it is more likely that they will act in a manner consistent with increasing cyber resilience. Three constructs for the individual level are included in this model:

Employee’s Self-Efficacy refers to a person’s knowledge about how well he or she can personally execute actions to increase cybersecurity. Bandura’s social cognitive theory, shows that people with high assurance in their capabilities consider difficult tasks as challenges to be mastered rather than as threats to be avoided. For example, when an individual feels his actions keep data safer, he is more likely to make the effort to do so, resulting in stronger cybersecurity attitudes.

Cybersecurity Policy Awareness is the individual’s knowledge of what behaviors the company seeks. It is knowing what to do, what is right or wrong and why it is important. It has been shown that unless employees understand a policy and what the policy means to them, the policy is not likely to improve cyber-safety for the organization. In strong cybersecurity cultures, employees understand policies and personal implications of the policies. For example, employees who know that their organization has a policy of locking a computer every time it’s left alone is more likely to believe that locking the computer is important.

General Cyber Threat Awareness refers to the individual’s knowledge and understanding of threats. Similar to the top management team’sknowledge about cybersecurity, the employee’s awareness about general cyber threat is an important factor to keep the organization secure because a cyber aware individual would be suspicious of unusual emails, texts, attachments, and other communications.

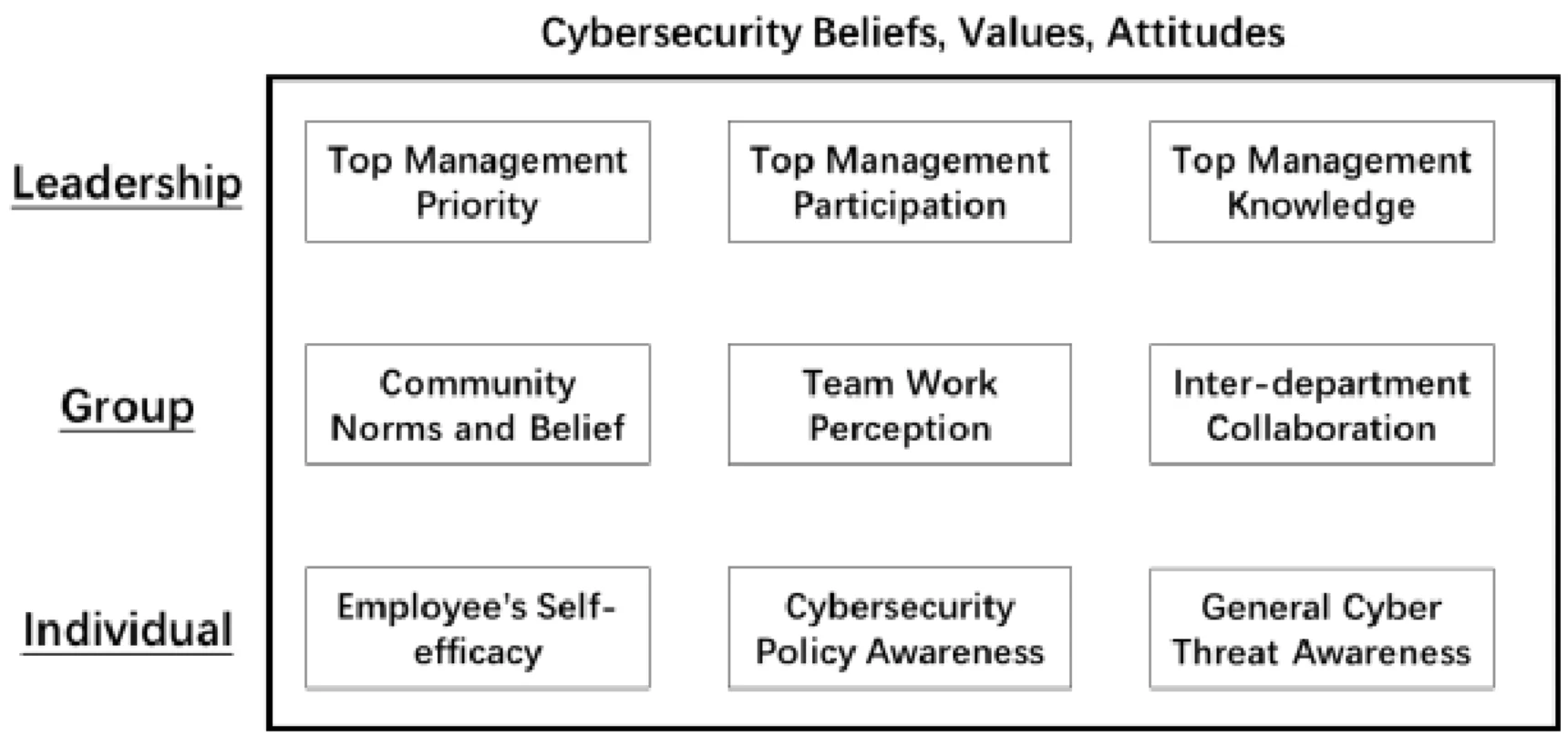

3.3. Organization Mechanisms

Beliefs, values, and attitudes comprise the unwritten rules and therefore the culture of the organization, but they are created by the actions of managers and leaders which we have labeled management levers or organizational mechanisms. Figure 3, identifies six managerial levers that managers can use to influence the cybersecurity culture. Managers make decisions on each of these levers, which in turn drive (and can be driven by) culture.

Cybersecurity Culture Leadership refers to the appointment of an individual or team with formal responsibility for building a cybersecurity culture. This leader has the responsibility to cultivate cybersecurity culture, and has the direct power and authority to impact the cultivation process. Though many organizations look to the CISOs to drive changes, someone other than the CISO, who has a very large agenda covering all aspects of cybersecurity culture, needs to be in this role. Without a leader with specific responsibility for building the culture, the activities will be haphazardly executed and sometimes skipped entirely.

Performance Evaluations refers to the inclusion of measures of cybersecurity compliance and behaviors in the employee’s formal evaluationprocesses. Expectancy theory shows that managers use the performance evaluation process to clarify what behaviors are required, nice to have, and not acceptable for the employees. For example, it might be unacceptable for employees to hand out system passwords to vendors without specific approval from upper management. In another example, employee evaluations might include the results of the phishing exercises regularly carried out by management. Including these measures in performance evaluations alerts employees about the organization’s ability to observe cybersecurity behaviors, which can in turn influences the employees’ values.

Rewards and Punishments refers to the managerial-generated impacts of cybersecurity behaviors. According to the rational choice theory, deterrence theory and the protection motivation theory, the design of the rewards and punishments can impact the individual decisions in many different contexts. Sample rewards include social events, proclamations, and certificates acknowledging exemplary behaviors, while punishments include remedial training, reprimands, or at an extreme, firing the offending employee. To be most effective, rewards and punishments must match the severity of the behavior. For example, failing a phishing test is probably not grounds for firing an employee. But in one company we studied an employee was fired for repeatedly and purposely failing phishing exercises. Management warned him several times, then let him go as concerns rose over his actions.

Organizational Learning refers to the ways the organization builds and retains cybersecurity knowledge. Organizational learning has been defined as “the intentional use of learning processes at the individual, group, and system level to continuously transform the organization in a direction that is increasingly satisfying to its stakeholders”. Organizational learning helps manage continuous change which is also characteristic of cybersecurity. Examples of organizational learning for cybersecurity include mentors who work with individuals to help them build skills, processes that encourage information sharing, consultants that bring new knowledge to the team, or subscriptions to information sharing services.

Cybersecurity Training refers to courses and exercises that develop cybersecurity skills and knowledge. Training fosters information security awareness, educates users on the importance of information security, and trains insiders to take on information security roles. Many organizations make new hires complete a cybersecurity training module as part of the onboarding process. Some organizations make employees take an annual update course or online training program to ‘refresh’ their knowledge of cybersecurity practices. Still other organizations have come up with additional training offerings such as just- in-time learning pop-up windows which teach a point in the learning moment. Our conversations with cybersecurity teams has indicated that just a single on- boarding training class is not sufficient to sustain long term behaviors; regular and varied training is needed.

Communications Channel refers to coherent, well-designed messages about cybersecurity communicated using multiple methods and networks. All successful business communications require that the right information is heard by the right person at the right time over the right channel. But what works for one person may not be the same for another. Managers must create multiple formal and informal channels for reporting cyber incidents, sharing dynamic cyber information, and even identifying potential vulnerabilities. For example, some organizations create cybersecurity-based marketing-like campaigns to influence behaviors by keeping the issues front and center for employees. Another example is to include short communication moments at the beginning of every company meeting to share a cybersecurity message.

3.4. External Influence

The attitudes, beliefs and values an individual or an organization has about cybersecurity are also shaped by external factors. For example, the more the public press reports on cyber breaches, the more aware individuals become of cyber risks. Furthermore, in some industries, the government or another regulating body dictates how companies must prepare and defend against cyber threats. For example, General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) regulations in Europe require organizations to assign a data protection officer so companies subject to this regulation will be more influenced than others. Three external influencers have significant impact on the culture of an organization:

Societal Cybersecurity Culture refers to the culture of the society in which an organization resides. The differences among nations and societies canimpact individual’s perception about online threat. For example, some countries have a strong societal value of protecting data. The beliefs of the organizations operating in that country would reflect that culture. Some organizations operate in a country with a more lasses-faire attitude, and we expect organizations in these countries to reflect this attitude in their cybersecurity culture.

External Rules and Regulations refers to the laws, guidelines, and regulations imposed by government and other industry organizations. Given the significant externalities in cyber security domain, the implementation of cybersecurity policies, from government agencies or powerful organizations such as supervisory authorities within an industry, can impact the organizational cybersecurity culture. For example, financial services companies are subject to very strict rules and regulations about managing their information and we expect those organizations to have different beliefs and attitudes towards cybersecurity than companies in other industries.

Peer Institutions refers to the pressure felt by managers in an organization from actions their peer organizations have taken. Institutional mimicry theory provides some support for this construct. It suggests that since cybersecurity is a relatively new threat with huge uncertainties for many organizations, managers often look to their peers for guidance on how to act. Trade associations, conferences, and simple social situations offer opportunities for managers to learn what options their peers have adopted. Additionally, as customers begin to seek out vendors with strong cybersecurity practices that match their supply chain requirements, organization are pressured to ‘up their cybersecurity game’ in order to compete. These would drive different attitudes about cybersecurity than those organizations with peers who are less concerned about these issues.

These four groups of constructs create a theoretical model that highlights the organizational cybersecurity culture--the beliefs, values and attitudes, in action. The full, expanded model is shown in Figure 4. The framework hypothesizes a number of relationships between mechanisms that managers can use to build a cybersecurity culture. Stated another way, the absence of these mechanisms is a potential indicator of a cybersecurity environment that exposes the organization to unnecessary risk. We envision managers using this framework to guide cybersecurity planning activities and investments. In the next section of this paper, we provide a rich case study to illustrate how one organization operationalized these constructs.

4. Case Study

To initially validate the model, we conducted an in- depth case study of a financial services company, Liberty Mutual Insurance. The data for this case study was collected over 6 months of structured interviews with key leaders and a small number of employees and from publically available documents about the company. Interviewees included the CISO and several members of his leadership team, and employees from marketing, training, support desk, and operations.

In this section we share the case study starting with the context, including the external influences in which Liberty Mutual operates. Then we share decisions managers have made on organizational mechanisms to drive a cybersecurity culture. The story continues with examples of the beliefs, values and attitudes created in their environment. We end the story with the behaviors driven by this culture.

4.1. Background, Context, and External Influences at Liberty Mutual

Boston-based Liberty Mutual Holding Company Inc. is the parent corporation of Liberty Mutual Insurance group, a diversified global insurer. According to their website, the company was the fourth largest property and casualty insurer in the U.S. LMHC employs more than 50,000 people in over 800 offices throughout the world[3]. As with many financial services organizations, managing cybersecurity to protect their data and their systems was a critical success factor.

Financial service firms invested in many technologies to protect their environment from cyber criminals. Not only were regulations in effect that financial services firms had to follow, but peer organizations invested significantly in technology to protect their systems and data. In 2017, technologies such as firewalls, intrusion and anomaly detection, password controls, and network auto shutdown mechanisms were commonplace solutions that provided some security for organizations such as Liberty Mutual. However, threat actors were advancing, using techniques, tactics and processes in new and more complex ways to breach the organization’s defenses. Even with the most sophisticated tools, the vulnerability created by human error or intent sometimes made the technology defenses simply inadequate. For example, phishing emails were increasingly sophisticated and, in some cases, targeted to specific individuals who held the keys to corporate system access (a practice called spear phishing).

Liberty Mutual and others in the financial services industry, were subject to strict external rules and regulations. US policies, like the New York Department of Financial Services (NYDFS) Cybersecurity Regulation, provide specific and prescriptive requirements this industry. Among NYDFS requirements, regulations called for cybersecurity awareness training for all personnel, updated to reflect risks identified in the company’s riskassessment.

Industry Peer Influence also helped shape ideas strategies to protect the systems and data of financial services firms. From banks to insurance firms to other players in the industry, protecting against cyber breaches and other vulnerabilities was paramount. No one wanted to do business with a firm who was not trustworthy nor capable of protecting investments. One executive commented:

"At the end of the day, the reputation of an insurance company is everything. People don’t want to do business with an insurance company they cannot trust".

4.2. Managerial Decisions: The Organizational Mechanisms

In the case of Liberty Mutual, the Chief Information Security Officer (CISO) and his team drove many activities to create a cybersecurity culture. Their actions established and reinforced values, attitudes and beliefs about the importance of digital and data security across the enterprise. The company invested a significant amount of resources to create this culture, establishing a global “Responsible DefenderTM” platform of messaging, communications, rewards, activities, and processes.

The CISO created a leadership position for cybersecurity culture, called the Product Owner, Cybersecurity Awareness, and charged her with creating and managing a culture of data protection (their term for cybersecurity culture). She took on the large tasks of creating messaging and other activities that drove a set of beliefs, values and attitudes to increase cyber resiliency. She explained:

“We found early on that everyone could relate to the term ‘data protection.’ Just a small change like using this term made a big difference in our efforts.”

Once this leader and her team were established, incentives to promote security culture and behavior were created. Early rewards and punishments were mainly associated with phishing exercises. Rewards and punishments were appropriate to the behavior and serve to motivate learning. One employee described the attitude towards the reprimands for clicking on the wrong email links:

“Sometimes people do click on the phishing links and then they have to take a training class. They are generally ok with that. We believe that our team members want to do the right thing and we are provided with all sorts of training and learning opportunities”.

The team took steps to measure this progress. Individual performance evaluations included discussions with managers about cybersecurity behaviors. If an employee failed a phishing exercise too often, it was reflected in their performance evaluation. If an employee went beyond their normal job requirements and helped others better understand how to help create a stronger culture of data protection that was noted, too.

The culture leader felt that cybersecurity training was best done through process of continual learning. The team developed training classes and communication campaigns. Almost every month, there were programs, called micro-campaigns, to increase awareness and security across the organization. During Cybersecurity Awareness Month, cybersecurity was made a larger corporate focus. In 2017, the U.S. core team rolled out a fun 20-minute training module across the enterprise. An Instructional Designer at Liberty Mutual, responsible for developing digital security training programs, elaborated:

"We made a decision to keep it light, engaging and not pedantic. We also use recent cultural references...our training also has to be fresh, current and relevant”.

Messaging was a key part of the Responsible DefenderTM Program. Liberty Mutual used multiple communications channels to transmit cybersecurity information. Traditional and instant learning opportunities, dynamic and engaging marketing campaigns, executive leadership, and highlighting rewards and consequences worked together to send a message of the importance of data protection. Messages were delivered using videos, digital displays, blogs, alerts, emails, post cards, events, and training. Although many different channels were used, communications were orchestrated to express consistent messaging. The culture leader and her team used the Responsible DefenderTM brand and traditional marketing techniques to spread cybersecurity messages throughout the company.

Additionally, major news stories often generated questions about cybersecurity which leaders at Liberty Mutual used with employees to raise awareness. This kind of organizational learning helped employees build and retain knowledge. For example, when the Equifax breach occurred in the summer of 2017, the information security team provided insight into what the breach meant, how it might impact an employee’s personal financial accounts, and what an employee might do to protect themselves. This made an impact on employees and helped them understand the value of cybersecure activities.

4.3. Liberty Mutual’s Culture of Data Protection

The result of leadership and managerial decisions encouraged cybersecure values, attitudes and beliefs that drove desired behaviors. To create their culture of data protection, employees at every level within the company demonstrated characteristics that matched the constructs in our model.

First, executives at Liberty Mutual made cybersecurity a top management priority. Leaders supported cybersecurity initiatives. They also demonstrated their priorities when they allocated significant resources for security tools and activities. Top management participation reinforced the importance of cybersecurity throughout the company. A set of regular blog posts from the CISO and his team were mapped out for the year to cover topics high on the security priority list. The CISO himself was the ‘face’ of the campaign. Employees saw a senior executive willing to be highly visible and personally involved in communicating the message and this encouraged them to pay attention. The management regularly worked to increase their cybersecurity knowledge of activities to protect their data. For example, executives understood that out of date software left an entryway for cyber criminals. Top management supported decisions to use the latest security software, use secure applications and install updates as often as possible to keep their technologies up to date.

At the group level, attitudes also reflected the culture of data protection. Slogans such as the “Responsible DefenderTM” and “Our Information. Our Responsibility” reinforced the general belief that cybersecurity is everyone’s responsibility, not just the responsibility of the technologies or cybersecurity professionals. These activities helped create strong community norms and beliefs. At Liberty Mutual, employees felt worked together to protect data. An employee elaborated on her perception of team work at the company:

"One example is the phishing exercises conducted throughout the year. We talk about them and compare notes like ‘did you click on that one?’"

This kind of group support went beyond single departments. Inter-department collaboration generated a strong sense of group culture. One cybersecurity leader described how:

"the success of creating a culture of data protection hinged on partnerships built with others across the enterprise...Being able to build alliances is a key to success in my role, and when it’s time to get the work done, we have gotten strong support from across the enterprise. ... Everyone on the core team ‘gets it’".

At the individual level, cybersecurity was clearly on the mind of a large number of employees. Many examples showed that employees personally did things to keep their data secure. Employee self-efficacy was demonstrated in interviews with employees who indicated that they felt empowered to protect the company’s data and information systems and theyunderstood actions they could take to do so. One employee shared stories about reporting suspicious emails to corporate authorities regularly.

Employees knew what to do in part because of a model called the Pillars of Data Protection, a simple to follow set of guidelines for all employees to follow. The Pillars were core concepts and behaviors information security leaders wanted all employees to adopt and interviews with employees demonstrated high levels of Cybersecurity Policy Awareness. The cybersecurity culture leader said:

"The Pillars of Data Protection give all of our employees a clear set of expected behaviors and things that need to be done continuously to protect our company,”

Their information security policy was written to make the policies more accessible and was further clarified with a section about “what this means to me” to translate policies into personal impacts. General cyber threat awareness was high at Liberty Mutual. In earlier surveys, information security managers found that most employees did not know who to ask questions of or what phishing was, among other issues. Managers regularly held discussions about cybersecurity issues that made newspaper headlines and communications campaigns sought to better inform employees of threats and of actions to take. Managers reported improvement in subsequent survey results.

4.4. Behaviors

Ultimately, Liberty Mutual leaders sought to instill the kinds of behaviors that would reduce risk and increase security. Initially the goal was to generate awareness of cyber resilience for every employee, not just in those in the IT department. Later the project moved beyond simply increasing awareness to encourage every employee to embed security actions into their in-role behaviors. Their investments paid off. Employees increasingly demonstrated behaviors in their day-to-day activities such as reporting suspicious activity, reduced clicks on phishing emails and securing personal technologies.

Additionally, since the Responsible DefenderTM Program emphasized cooperative helping and voicing behavior employees exhibited extra-role behaviors in the larger community. The cybersecurity leader described how this played out:

“Everyone thinks of themselves as ‘first responders’ and they will alert us if they see a suspicious email or other activity...They see it as learning more about what to do or not to do and they don’t feel bad about it. It provides more motivation to get it right in the future.”

5. Discussion and Conclusion

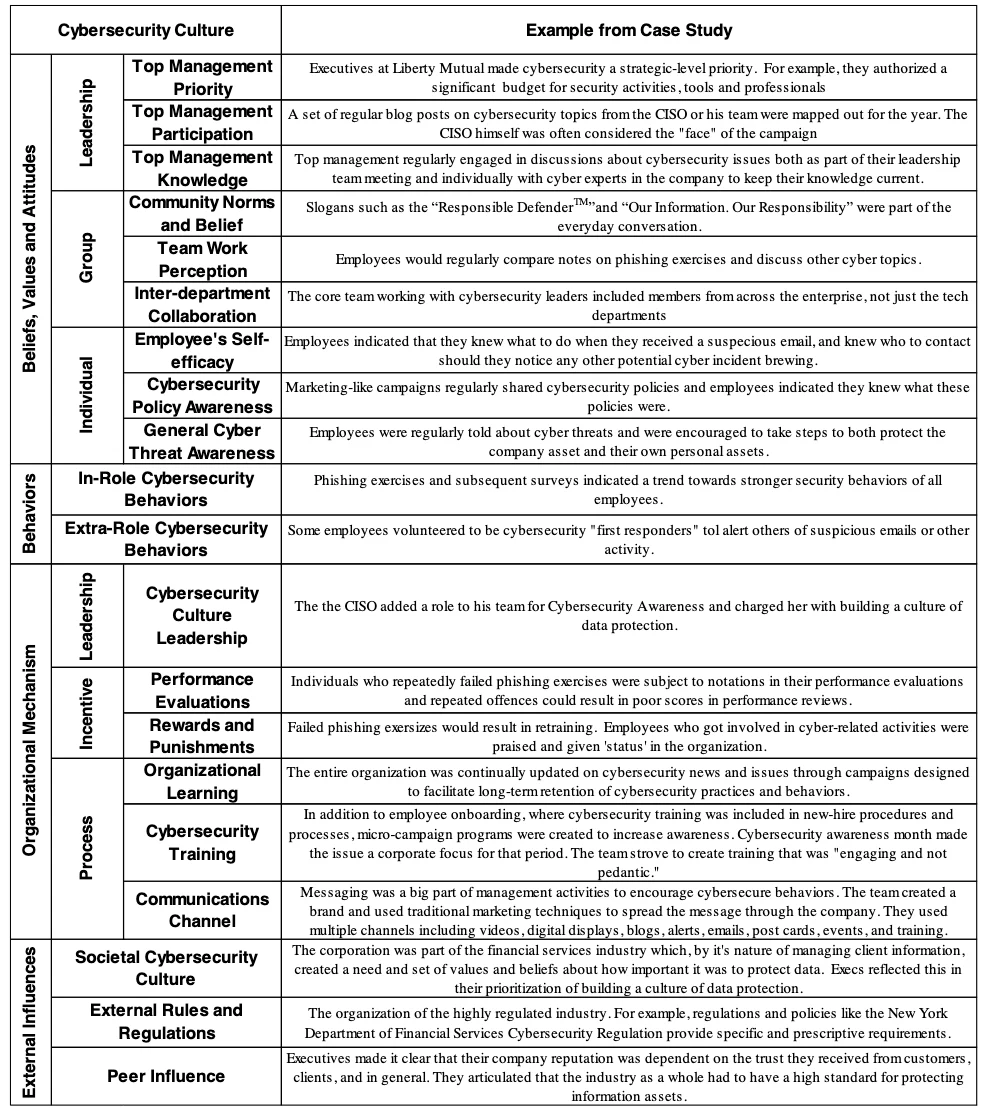

Liberty Mutual leaders wanted to minimize human behaviors that create cybersecurity vulnerability and increase behaviors that protect their company. In addition to installing the latest security software, and keeping their technologies up to date, etc., leaders made decisions that influenced attitudes, beliefs and values around cybersecurity. Communications focused on awareness and action. The goal was for all employees to understand their individual responsibility for cybersecurity, and early indicators suggested that these investments were paying off. Table 1 summarizes examples for each of the model constructs from the Liberty Mutual case study.

Becoming a cyber-resilient organization is a combination of both technology and organizational investment. All the technology available to secure systems will not keep an organization secure if the people in the organization make bad or uninformed decisions that open up the system to threat actors. Yet managers continue to invest in upgraded technologies and, in many cases, resist investments in organizational mechanisms that would increase resilience.

This research suggests a number of ways managers can help build a culture of cybersecurity, and how an organization can evaluate if their culture drives cyber secure behaviors. Behaviors are driven by unwritten rules, which are difficult to see. But the artifacts of those unwritten rules are apparent in the values, beliefs and attitudes displayed by management, teams and individuals in the organization. This research articulates a model of constructs that managers can use to observe their cybersecurity culture, and the Liberty Mutual Case Study describes specific ways one leading organization operationalizes this model.

Managers can further strengthen the values, beliefs and attitudes around cybersecurity through decisions they make about performance, control, and governance systems. This work highlights six levers for managers to use such as building cybersecurity expectations in performance evaluations and reward systems, enforcing consequences for insecure performance, creating strong communications plans, and providing ongoing training and updated opportunities for learning about increased cybersecurity activities. All are actions any manager in an organization can take to strengthen cyber resiliency. Further, when management creates a position specifically dedicated to creating a cybersecurity culture, they can expect to see results that increase resilience in the organization.

Increasing cyber-resilience is on every executive agenda, and this project will help leadership teams and all levels of management identify specific ways they can aid their organization in achieving this objective.

References

[1] P. R. Clearinghouse, “Data Breaches,” 2018. [Online].

[2] Ponemon Institute LLC, “2018 Cost of Data Breach Study, Global Overview,” IBM Secur., no. July, pp. 1–34, 2018.

[3] K. Huang, M. Siegel, and S. Madnick, “Systematically Understanding the Cyber Attack Business: A Survey,” ACM Comput. Surv., vol. 51, no. 4, 2018.

[4] K. Pearlson and K. Huang, “Liberty Mutual: Creating a Culture of Data Protection,” 2018.

[5] B. Gardiner, “Johnson & Johnson champion people-based security strategy.,” CIO (13284045), 24-Mar-2015. [Online].

[6] D. E. Leidner and T. Kayworth, “Review: A Review of Culture in Information Systems Research: Toward a Theory of Information Technology Culture Conflict,” MISQ Rev., vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 357–399, 2006.

[7] A. Da Veiga, “A cybersecurity culture research

philosophy and approach to develop a valid and reliable measuring instrument,” in Proceedings of 2016 SAI Computing Conference, pp. 1006–1015.

[8] R. A. Carrillo, “Positive Safety Culture,” Prof. Saf., vol. 55, no. 5, p. 47, 2010.

[9] E. H. Schein, Organizational culture and leadership, vol. 2. John Wiley & Sons, 2010.

[10] J. J. van Muijen and E. Al, “Organizational Culture: The Focus Questionnaire,” Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol., vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 551–568, 1999.

[11] G. Hofstede, “Cultural dimensions in management and planning,” Asia Pacific J. Manag., vol. 1, no. January, pp. 81–99, 1984.

[12] A. Da Veiga and J. H. P. Eloff, “A framework and assessment instrument for information security culture,” Comput. Secur., vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 196–207, 2010.

[13] NIST, “Glossary of Key Information Security Terms,” NISTIR 7298 Rev.2. [Online].

Footnotes

Due to space limitations, we have not included all the related references. Instead, this paper focuses on topics that are more informative for practice: the model and the case study. Additional references are available from the authors.

Due to space limitations and the disclosure policy requirement, these practices are not publicly available nor included in this version but will be available upon request though emailing to the author. These participants are from members of Cybersecurity at MIT Sloan. Please check the CAMS website for the member list.

https://www.libertymutualgroup.com/about-liberty-mutual-site/investor-relations-site/Documents/Q4_2017_LMG_Fact_Sheet.pdf